Weeeeeeeeekende!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Lucky sez, "ZZzzzzzzZZZzzzzzzzzZZZZZzzzzzzzZZZZZZZZzzzzzzzzzzzzzZZZZZZZZZZZzzzzzzzzz ... "

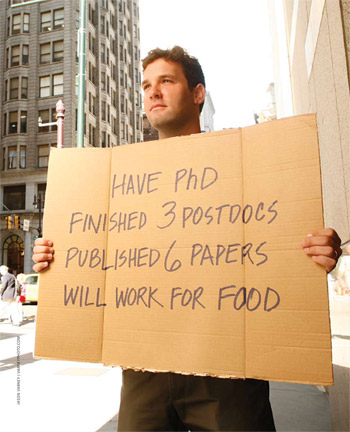

"In many disciplines, for the majority of graduates, the Ph.D. indicates the logical conclusion of an academic career." Marc Bousquet

Friday, September 30, 2011

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

On Style (Outside Academe)

No, I'm not talking about clothing (though I did have some fun at the mall this weekend). Rather, when it comes to style guides for writing, whether you are inside or outside academe, the rule of thumb to remember is consistency.

Inside academe, when I taught students MLA style, I would always caution them that not all disciplines used MLA style, that they'd have to accustom themselves to whatever style guides were favored by their majors.

I should have said something about the nonacademic world, too.

The other day, Think Tank had a meeting about style. Apparently, that's a problem here in all kinds of different publications, publicly circulated documents, and funding proposals. People are inconsistent. They don't pay attention to simple things like getting the office address correct. They write like they talk. They abuse punctuation. They represent Think Tank as a "we" rather than an "it."

So, Chief Editor and some others put together a Think Tank Style Guide, a manifestly entertaining pastiche of Chicago Style, AP Style, and Think Tank stylistic idiosyncracies boldly defended as "the right way."

Aside from the mildly irritating fact that nobody gave a damn what I had to say on the subject (go figure), they did have a point about consistency. Really, since Think Tank is not an academic institution, the academic style guides are not always appropriate, and, likewise, since it is not a press organization, AP style is not always best. So, it makes sense to come up with a guide that is neither of these things but yet reflects the needs of the organization in terms of public image and voice and at least encourages consistency among the large numbers of people who write within the organization for a wide variety of outlets and contexts.

While I don't necessarily agree with all the "guidelines," I'm willing to go along with them for the sake of consistency. Here's the thing, though: I don't actually write here. I just edit, mostly just Think Tank Boss's work. And Think Tank Boss, according to Chief Editor, is one of the worst offenders, a problem that often crops up among good writers who have a distinctive voice and don't want to sacrifice saying what they have to say in the way they want to say it to the demeaning imposition of stylistic regulation. I can edit TTB's work for consistency out the wazoo, but, if ze chooses hir own style rather than Think Tank style, ze will simply reject my edits.

Which is fine. Ze has the right to do that. But, where does that leave me as the editor? Chief Editor (and the rest of them) will think, "How can you have a Ph.D. in English and be too stupid to follow a style guide?" TTB should have attended the style meeting hirself.

Moreover, when you think about it, no matter what the context, Think Tank really is an "it" and not a "we." Usage of "we" is a powerful tool that establishes a writer's ethos by uniting hir voice with the authority of other voices. But in what context is this appropriate? There are always exceptions, but, generally, as far as I can tell, situations here at Think Tank with a rhetorical imperative to violate this rule are rare. Logically, only in those situations in which the entire organization really is speaking collectively or when Think Tank partners with other groups and all the groups together form a "we" should writers employ this pronoun.

Harruuuumph. I think Grammar Girl would have something to say, too.

Inside academe, when I taught students MLA style, I would always caution them that not all disciplines used MLA style, that they'd have to accustom themselves to whatever style guides were favored by their majors.

I should have said something about the nonacademic world, too.

The other day, Think Tank had a meeting about style. Apparently, that's a problem here in all kinds of different publications, publicly circulated documents, and funding proposals. People are inconsistent. They don't pay attention to simple things like getting the office address correct. They write like they talk. They abuse punctuation. They represent Think Tank as a "we" rather than an "it."

So, Chief Editor and some others put together a Think Tank Style Guide, a manifestly entertaining pastiche of Chicago Style, AP Style, and Think Tank stylistic idiosyncracies boldly defended as "the right way."

Aside from the mildly irritating fact that nobody gave a damn what I had to say on the subject (go figure), they did have a point about consistency. Really, since Think Tank is not an academic institution, the academic style guides are not always appropriate, and, likewise, since it is not a press organization, AP style is not always best. So, it makes sense to come up with a guide that is neither of these things but yet reflects the needs of the organization in terms of public image and voice and at least encourages consistency among the large numbers of people who write within the organization for a wide variety of outlets and contexts.

While I don't necessarily agree with all the "guidelines," I'm willing to go along with them for the sake of consistency. Here's the thing, though: I don't actually write here. I just edit, mostly just Think Tank Boss's work. And Think Tank Boss, according to Chief Editor, is one of the worst offenders, a problem that often crops up among good writers who have a distinctive voice and don't want to sacrifice saying what they have to say in the way they want to say it to the demeaning imposition of stylistic regulation. I can edit TTB's work for consistency out the wazoo, but, if ze chooses hir own style rather than Think Tank style, ze will simply reject my edits.

Which is fine. Ze has the right to do that. But, where does that leave me as the editor? Chief Editor (and the rest of them) will think, "How can you have a Ph.D. in English and be too stupid to follow a style guide?" TTB should have attended the style meeting hirself.

Moreover, when you think about it, no matter what the context, Think Tank really is an "it" and not a "we." Usage of "we" is a powerful tool that establishes a writer's ethos by uniting hir voice with the authority of other voices. But in what context is this appropriate? There are always exceptions, but, generally, as far as I can tell, situations here at Think Tank with a rhetorical imperative to violate this rule are rare. Logically, only in those situations in which the entire organization really is speaking collectively or when Think Tank partners with other groups and all the groups together form a "we" should writers employ this pronoun.

Harruuuumph. I think Grammar Girl would have something to say, too.

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Ponderable

More people visit this blog in a day than will probably ever "visit" any of my academic publications in the course of my lifetime.

Friday, September 23, 2011

My Analysis of This Year's Academic Job Market Insanity

A it turns out, the Academic Jobs Wiki has the job listings up that I was grousing about in my previous post (I tend to overreact to things that piss me off), and, based on my ability to compare the wiki to the JIL last year, I think it's pretty accurate. At least, I don't think I'm missing anything important.

So, here's my take on the job situation this year (which was what I was going to write about earlier, had I not had to confront yet another slap in the face from Establishment Academe):

Barring comp positions, generalist positions (although I may give these another look later), VAPs, and postdocs, there are exactly 28 jobs across the U.S. for which, broadly speaking, I am qualified to apply.

That's about what it was last year, and, no, reader, that is not "good." That is not even kinda sorta OK. If there were 30 or 50 or even 200 people seeking these jobs, then maybe it would be OK. But last year, I got letters back saying I was one of 450, 500, 600, and in one case, 700 applicants. That is not "OK." That is .... is there a word that means bleaker than bleak? Because, in addition to everyone that didn't get hired last year, there is now a whole new bright-eyed, bushy-tailed crop of ABDs and recent PhDs headed out on the market.

Now, as if that weren't bad enough, all of those 28 jobs are not actually a good "fit" for me. The post-academic blogosphere lately has been a-buzz with discussions of what constitutes "fit," but on the simplest level, "fit" is about your sub-specializations. Those 28 jobs are grouped together on the job lists by nation and time period, and based on ONLY nation and time period, I am a good match for all of them. Indeed, in a "normal" job market (was there ever such a thing?), you'd expect that someone with a Ph.D. in a particular language and literature would have a chance at getting hired for a position that had a concentration in EITHER fiction or poetry. Or drama, for that matter. And certainly, in terms of my teaching experience, I could make a case for my proven ability to teach in any of these areas. But, alas, my dissertation and publications only deal with one of them. And so, in a candidate pool of (let's be on the generous side here) 600 people, my application is getting tossed out -- no matter how brilliant I am -- right off the bat if my specialty is fiction and the job specifies poetry and 300 of those 600 applicants wrote their dissertations on poetry. Why would I waste my time and money and effort? (And yet, that is the advice job seekers are given when advisers say, "Apply to anything and everything for which you are remotely qualified -- you never know!" Bullshit.)

Add to the poetry/fiction/drama distinction specialty indications in various more narrow time periods. Instead of the 19th c., for example, an ad might specify "the 19th c. with preference given to those whose work focuses on the Romantics." If your dissertation is on the Realists or Naturalists, you're fucked and you should just not bother, even if you know a thing or two about the Romantics and wouldn't mind taking your research in that direction. And, further, there are preferences expressed for specialization in various regional and ethnic literatures. Even if you have an interest in X, taught a course with a unit on X, wrote a chapter of your dissertation on X, there are umpteen hundreds of candidates who did their whole dissertations on X. Don't waste your time.

So, let's recalibrate. The new number of jobs for which I am qualified to apply, readjusted for these various sub-specializations, is 13.

That's right, kids, a whopping 13 jobs for how many hundreds of applicants?

YeeaaaAAAAHHHHHHH!!!!!!!

Here are a few more things worthy of note:

However, friends, while I may be casting about one more time, I really have no expectations. As I've said before, I like teaching, I like research, I like writing. I would like to be able to do these things as my job -- and to get paid for doing them as my job, well, let's start with at least as much as I'm earning as a secretary ... and that ain't much!

For all that I might like such a job, I am also more than well aware -- now much more so than I was the first time I went on the market (this is my 3rd time) -- that this profession is seriously dysfunctional and that taking such a job in certain environments is ethically unsound.

So, we'll see. Some afternoon when Think Tank Boss is on the road, I'll put together my 5-6 applications and send them out, and then I will forget about all of this nonsense. If something comes of it? Fine, we'll take that step by step. If nothing comes of it? Fine. I will be done with this parody of a profession once and for all. I will cast my career lot elsewhere and pursue my research and writing interests independently.

And, friends, this is about as sane a take as I can possibly hope to offer you on the insanity that is the academic job market.

So, here's my take on the job situation this year (which was what I was going to write about earlier, had I not had to confront yet another slap in the face from Establishment Academe):

Barring comp positions, generalist positions (although I may give these another look later), VAPs, and postdocs, there are exactly 28 jobs across the U.S. for which, broadly speaking, I am qualified to apply.

That's about what it was last year, and, no, reader, that is not "good." That is not even kinda sorta OK. If there were 30 or 50 or even 200 people seeking these jobs, then maybe it would be OK. But last year, I got letters back saying I was one of 450, 500, 600, and in one case, 700 applicants. That is not "OK." That is .... is there a word that means bleaker than bleak? Because, in addition to everyone that didn't get hired last year, there is now a whole new bright-eyed, bushy-tailed crop of ABDs and recent PhDs headed out on the market.

Now, as if that weren't bad enough, all of those 28 jobs are not actually a good "fit" for me. The post-academic blogosphere lately has been a-buzz with discussions of what constitutes "fit," but on the simplest level, "fit" is about your sub-specializations. Those 28 jobs are grouped together on the job lists by nation and time period, and based on ONLY nation and time period, I am a good match for all of them. Indeed, in a "normal" job market (was there ever such a thing?), you'd expect that someone with a Ph.D. in a particular language and literature would have a chance at getting hired for a position that had a concentration in EITHER fiction or poetry. Or drama, for that matter. And certainly, in terms of my teaching experience, I could make a case for my proven ability to teach in any of these areas. But, alas, my dissertation and publications only deal with one of them. And so, in a candidate pool of (let's be on the generous side here) 600 people, my application is getting tossed out -- no matter how brilliant I am -- right off the bat if my specialty is fiction and the job specifies poetry and 300 of those 600 applicants wrote their dissertations on poetry. Why would I waste my time and money and effort? (And yet, that is the advice job seekers are given when advisers say, "Apply to anything and everything for which you are remotely qualified -- you never know!" Bullshit.)

Add to the poetry/fiction/drama distinction specialty indications in various more narrow time periods. Instead of the 19th c., for example, an ad might specify "the 19th c. with preference given to those whose work focuses on the Romantics." If your dissertation is on the Realists or Naturalists, you're fucked and you should just not bother, even if you know a thing or two about the Romantics and wouldn't mind taking your research in that direction. And, further, there are preferences expressed for specialization in various regional and ethnic literatures. Even if you have an interest in X, taught a course with a unit on X, wrote a chapter of your dissertation on X, there are umpteen hundreds of candidates who did their whole dissertations on X. Don't waste your time.

So, let's recalibrate. The new number of jobs for which I am qualified to apply, readjusted for these various sub-specializations, is 13.

That's right, kids, a whopping 13 jobs for how many hundreds of applicants?

YeeaaaAAAAHHHHHHH!!!!!!!

Here are a few more things worthy of note:

- Among those original 28 jobs is one at Grad U, a job in an area in which there must be at least 50 adjuncts who would kill for a chance to prove themselves on the tenure track. Grad U, you motherfuckers, why don't you promote an adjunct, somebody that already has a proven track record of teaching in the department?

- Of the 13 jobs that "fit" me, only 5-6 actually interest me (a variety of idiosyncratic reasons).

- Salaries aren't listed for most of the jobs, but there are some. These jobs describe themselves as "competitive," but, from where I'm sitting right now with a glimpse of the Great Nonacademic Beyond, they seem more pathetic than competitive, especially if you're asking somebody to pick up and move across the country. You know who a salary of $50K for teaching 4/4 might seem "competitive" to? Burned out, impoverished adjuncts, that's who. You see how this works? This SYSTEMIC problem of labor exploitation is already affecting assistant profs, the group that comprises the next step up in the hierarchy after adjuncts. If you're comfortably situated on the tenure track now and don't think the problems of current job seekers are relevant to you, think again. If you care at all about the future of the profession, you should be getting involved in changing the system.

However, friends, while I may be casting about one more time, I really have no expectations. As I've said before, I like teaching, I like research, I like writing. I would like to be able to do these things as my job -- and to get paid for doing them as my job, well, let's start with at least as much as I'm earning as a secretary ... and that ain't much!

For all that I might like such a job, I am also more than well aware -- now much more so than I was the first time I went on the market (this is my 3rd time) -- that this profession is seriously dysfunctional and that taking such a job in certain environments is ethically unsound.

So, we'll see. Some afternoon when Think Tank Boss is on the road, I'll put together my 5-6 applications and send them out, and then I will forget about all of this nonsense. If something comes of it? Fine, we'll take that step by step. If nothing comes of it? Fine. I will be done with this parody of a profession once and for all. I will cast my career lot elsewhere and pursue my research and writing interests independently.

And, friends, this is about as sane a take as I can possibly hope to offer you on the insanity that is the academic job market.

|

| Via |

Your MLA Membership Is No Longer Enough to Get You Access to the Job Information List

Dear MLA:

I have been a member of your organization for the last decade. Paying my dues while in graduate school was a sacrifice, but I kept up with them because I valued the work you do for the profession. Not only that, but I've contributed to the life of the organization and the profession by presenting on panels at several different annual conventions.

To date, I remain a member in good standing, but I renewed my membership this year primarily because I wanted access to the Job Information List. Sadly, once I finished graduate school and was no longer still a "student," I had to quit my job as an adjunct because I couldn't support myself on the salary and could no longer, in good faith, take handouts from my family. Indeed, had I not had a supportive partner and family, I may well have faced the prospect of food stamps while an adjunct. Choosing to take a nonacademic position was a no-brainer, but, at the same time, I'm still on the fence about whether I want to pursue a career as a professor. At the very least, I wanted to take a good look at this year's JIL, decide if there were any positions for which I seemed a good enough "fit" to apply, and, if there were, go ahead and apply for them.

So, when I finally made my way over to your website today and logged in, I was extremely disappointed and exasperated to find the following statement posted:

I can only conclude that the MLA is choosing to reinforce its complicity with the system of contingent faculty serfdom that plagues this profession. As long as we continue to work as adjunct serfs, the MLA is more than willing to gift us with the privileges of "affiliation." But challenge the hierarchy and the system by opting out, and oops! Sorry!! No more JIL for you!!! You must have given up. Only people who still BELIEVE are welcome. You must BELIEVE enough in The Profession to sacrifice your dignity and well-being, and perhaps then we will condescend to offer you a MERE LOOK at the list of this year's jobs, many of which you are more than qualified for but none of which you will ever be a good enough "fit" to have.

Really, what does the "privilege" of viewing the JIL do for us anyway but reinforce the delusion that, this year, there is "hope," that, this year, all is not "bleak" -- that, this year, we might find the "right" job for which we are the perfect "fit," and that, indeed, this year offers ever so much more promise for a better future in the profession than last year did?

If MLA leadership really cared about EVERYONE in this profession and not just those within the tenure system, they would be encouraging adjuncts to do just what I've done and walk away -- that is, until pay and working conditions improve. They would be more actively promoting alternative careers for Ph.D.s. They would be seriously involved in supporting efforts to shrink graduate programs.

But what would happen if more of us -- if large numbers of us -- were to "just say no" to disgracefully low pay, no job security, no benefits, and no opportunities for promotions and raises despite good performance? What would happen is that compensation for ALL faculty positions would have to become more competitive, that the tenure system would have to be reevaluated and made more just, and that both universities and our society more generally would have to reckon more seriously with the REAL costs of higher education.

All of which would mean publicly questioning the myth of meritocracy that props up the current system of rank and privilege. After all, how would those on the tenure track know just how special they were if it weren't for the bilious masses on the adjunct track who, year after year after pathetic year, look hopefully to the JIL, like Tantalus, for the fruit of respectable employment that is forever out of reach?

So, what am I going to do? Am I going to pay the extra $80 to join the ADE? I don't know. I will probably, at the very least, take a good, hard look at the postings at Inside Higher Ed first. And you know what else? I figured I'd just continue to renew my dues every year, at least until I figured out what this business of being an "independent scholar" meant for my post-academic life, but fuck that, MLA. Don't count on me to renew my membership and waste even more money on dues in 2012.

Best,

recent Ph.D.

I have been a member of your organization for the last decade. Paying my dues while in graduate school was a sacrifice, but I kept up with them because I valued the work you do for the profession. Not only that, but I've contributed to the life of the organization and the profession by presenting on panels at several different annual conventions.

To date, I remain a member in good standing, but I renewed my membership this year primarily because I wanted access to the Job Information List. Sadly, once I finished graduate school and was no longer still a "student," I had to quit my job as an adjunct because I couldn't support myself on the salary and could no longer, in good faith, take handouts from my family. Indeed, had I not had a supportive partner and family, I may well have faced the prospect of food stamps while an adjunct. Choosing to take a nonacademic position was a no-brainer, but, at the same time, I'm still on the fence about whether I want to pursue a career as a professor. At the very least, I wanted to take a good look at this year's JIL, decide if there were any positions for which I seemed a good enough "fit" to apply, and, if there were, go ahead and apply for them.

So, when I finally made my way over to your website today and logged in, I was extremely disappointed and exasperated to find the following statement posted:

I was already well aware of how individual institutions privilege affiliation, but why, when you allow me to join the MLA as an "independent scholar," do I need FURTHER affiliation to access the JIL? At the time that I renewed my membership for 2011 at a cost of $70, I was NOT informed that I would have to pay MORE, an additional $80 (!), to have access to the JIL. I identified myself at the time as an "independent scholar" (I could have lied) and, given that dues are progressive and based on income, I was honest about choosing the appropriate income category (again, I could have lied). There was NOTHING about having to join an ADDITIONAL professional organization -- for a profession about which I already have serious misgivings -- in order to view an MLA resource.Beginning in August, if you are not in a member department, you may join ADE [Association of Departments of English] as an affiliate member to receive access to the JIL.

I can only conclude that the MLA is choosing to reinforce its complicity with the system of contingent faculty serfdom that plagues this profession. As long as we continue to work as adjunct serfs, the MLA is more than willing to gift us with the privileges of "affiliation." But challenge the hierarchy and the system by opting out, and oops! Sorry!! No more JIL for you!!! You must have given up. Only people who still BELIEVE are welcome. You must BELIEVE enough in The Profession to sacrifice your dignity and well-being, and perhaps then we will condescend to offer you a MERE LOOK at the list of this year's jobs, many of which you are more than qualified for but none of which you will ever be a good enough "fit" to have.

Really, what does the "privilege" of viewing the JIL do for us anyway but reinforce the delusion that, this year, there is "hope," that, this year, all is not "bleak" -- that, this year, we might find the "right" job for which we are the perfect "fit," and that, indeed, this year offers ever so much more promise for a better future in the profession than last year did?

If MLA leadership really cared about EVERYONE in this profession and not just those within the tenure system, they would be encouraging adjuncts to do just what I've done and walk away -- that is, until pay and working conditions improve. They would be more actively promoting alternative careers for Ph.D.s. They would be seriously involved in supporting efforts to shrink graduate programs.

But what would happen if more of us -- if large numbers of us -- were to "just say no" to disgracefully low pay, no job security, no benefits, and no opportunities for promotions and raises despite good performance? What would happen is that compensation for ALL faculty positions would have to become more competitive, that the tenure system would have to be reevaluated and made more just, and that both universities and our society more generally would have to reckon more seriously with the REAL costs of higher education.

All of which would mean publicly questioning the myth of meritocracy that props up the current system of rank and privilege. After all, how would those on the tenure track know just how special they were if it weren't for the bilious masses on the adjunct track who, year after year after pathetic year, look hopefully to the JIL, like Tantalus, for the fruit of respectable employment that is forever out of reach?

So, what am I going to do? Am I going to pay the extra $80 to join the ADE? I don't know. I will probably, at the very least, take a good, hard look at the postings at Inside Higher Ed first. And you know what else? I figured I'd just continue to renew my dues every year, at least until I figured out what this business of being an "independent scholar" meant for my post-academic life, but fuck that, MLA. Don't count on me to renew my membership and waste even more money on dues in 2012.

Best,

recent Ph.D.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

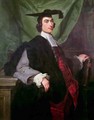

Academic Fantasy vs. Reality

Unfortunately, a great many people -- both inside and outside of academe -- imagine an academic's life to be very different from what it is for most academics these days. Fantasies of what academic life is supposed to be like come from a host of sources: books, movies, personal experiences both good and bad, observation limited by factors from familial relationships to socioeconomic privilege to willful self-delusion.

Before you can begin to extricate yourself from academe -- if only from the exploitative danger of its myths -- you must begin to examine your own fantasies and expose them for what they are.

What were my fantasies and where did they begin? I offer this evidence in the hope that it might stimulate you to think about your own academic fantasies vs. the reality behind them -- and those of your friends and family and advisers and all the rest of the people who don't understand why you've gone so far only to walk away. It isn't the only experience that affected my distorted perceptions of academe, but it's a good place to start.

Before you can begin to extricate yourself from academe -- if only from the exploitative danger of its myths -- you must begin to examine your own fantasies and expose them for what they are.

What were my fantasies and where did they begin? I offer this evidence in the hope that it might stimulate you to think about your own academic fantasies vs. the reality behind them -- and those of your friends and family and advisers and all the rest of the people who don't understand why you've gone so far only to walk away. It isn't the only experience that affected my distorted perceptions of academe, but it's a good place to start.

* * * * *

When I was growing up, one of my adult relatives whom I admired and liked the most was my dad's brother-in-law, my uncle, a professor at a small liberal arts college (SLAC). During the summers, my aunt and uncle would stay at their summer cottage on One of the Great Lakes, and my parents, who were K-8 teachers, would often take my brother and me there to spend a week or two visiting. The cottage was part of a collective of 10 or so other cottages, and though but the humble relics of what had been something like a hippie commune in the 60s, these cottages were located on a property that included a private beach. It was idyllic. It was rustic. It was the kind of place where, if you were a kid, your imagination might play tricks on you as you watched the sunset over the lake.

The lake itself was mesmerizing, sometimes still as glass, sometimes turbulent. The air was intoxicatingly fresh. And the beach and forest smells blended with dinner on the grill and my uncle's tobacco pipe ... the sounds of the waves with carefree laughter ... things I dreamed with things that were real ...

Needless to say, I loved it there, but while most of the adults chattered away and the kids played games or splashed around in the water, my favorite pastime was sitting in a lounge chair -- on the land just above but overlooking the beach -- under a big, shady tree reading a book.

My uncle was always reading, too. His books were scattered all over the cottage, on shelves, tables, chairs, the floor. At night, as I was falling asleep on a cot in the living room area, after everyone else had gone to sleep, I could hear him typing away on an old-fashioned typewriter by the light of a small desktop lamp, pipe smoke drifting across the cottage, out the window and into the night.

No one else paid any attention to me and my reading. But, while not much of a talker, my uncle would ask me what I was reading: "Oh," he would say, scratching his chin, "That's a good one. What a great writer! I'm so glad you're reading this. Have you read Other Book by Famous Author? No? Oh, well you should when you finish this one. In fact, I think we have a copy in the cottage ... " And then he would pat me on the shoulder or the top of the head, as if to say, "Aw, what a good kid," puff on his pipe and wander off, lost in his own thoughts, and I'd go back to my book.

I saw my uncle as a sort of kindred spirit during those summers, and for a long time the very small glimpse I got of his life as a professor colored my perception of what life as a professor was like for everyone. When I thought of becoming a professor myself, long before I'd even finished high school, I thought about my uncle. I wanted to do what he did (read books, think deep thoughts, write arcane essays). I wanted a life like his life (summers on the beach, winters on a quaint campus in Connecticut, a tweed jacket, a fragrant pipe, a comfortable office, distinguished colleagues, witty friends ....... my aunt in the kitchen taking care of the children?)

* * * * *

Wait. "What?" you say. Yes, exactly. Cooking? Children? Housework? There were things about my uncle's life as a professor that I simply missed. My aunt's role was one of them. She took care of everything related to home and children so that he could be "free" to think his deep thoughts, teach his classes, and write his books. My aunt was one of those "faculty wives" back in the 60s and 70s as my uncle was building his career. I don't know how she felt about this role, but it is certainly true that his success wouldn't have been possible without her willingness to fulfill this role.

There were other things, too ... my uncle, of course, began his career in the late 60s when there were still jobs aplenty. A call from your adviser, supposedly, was all it took. But even then (and I didn't know this until much later, well into my own grad school years), he spent several years as a VAP at two different institutions, as well as a year as a postdoc somewhere else, moving his young family all around the country before finally landing a tenure-track job. But the way my parents talked about it, he had simply "taught" at these different places. They made no distinction because they themselves didn't understand academic hierarchies. My uncle, retired now, was the only professor in our family and the only one with a Ph.D., until I got mine (though we do also have a few medical doctors).

And the cottage on the lake? The large, nicely appointed house in Connecticut?? I don't know what my uncle earned at any of his faculty jobs, but he was a full professor at the liberal arts college when he retired. I'm sure his salary was comfortable enough. The thing that I didn't know, though -- again, not until much later -- was that whatever he was earning, it didn't really matter all that much. Nor did job security. Nor benefits. Not really. His mother, I learned, was quite well off. He had a good relationship with her, and he knew that she (and her house and resources) were available to him should he and his wife and children ever need them. Moving across the country for a one-year VAP appointment with no assurance of employment beyond that term? No problem if it doesn't work out. There's always Mom. Taking a postdoc that doesn't pay enough to support that second kid that's on the way? No problem, Mom can help out.

When his mother died about 25 years ago, she left everything to my uncle. He could afford to live the "life of the mind."

But as opportunities have become even scarcer than they were for my uncle's generation, as academic life has become even more precariously contingent, it is ONLY people like my uncle who can afford the sacrifices.

* * * * *

The purpose of this post is not to belittle my uncle. He's still one of my favorite relatives. He and my aunt still have the cottage on the lake, and Peaches and I still go now and then to visit. But my uncle's reality is not mine. The "opportunities" he took advantage of early on -- the postdoc and the VAPs -- no longer carry the career-furthering weight they once did, and I don't have the luxury of leaving it up to fate and "fit."

And that is why it is important to separate the fantasy of the "gentleman scholar" from the reality of poverty and job insecurity that the majority of younger academics face today.

|

| Via |

(Oh, and if you are into symbolic evidence, there was that pipe smoking ... but not anymore. Lung cancer. He survived and has been cancer free for several years now, but he lost a lung, too ... )

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Honey Badger Don't Give a Shit About the MLA Job Information List

So, word has it that the MLA Job Information List is up. Awesome! I haven't troubled myself to look yet, but if you have and are freaking out at what's out there (or, like NOT out there!) and the whole prospect of writing all those shitty letters and sending out your materials for shitty jobs you could give a shit about but think you desperately want anyway ... well, I got news for you!

The Honey Badger could give a shit about the JIL, and you, friends, need to be a little more like The Honey Badger. Just watch this video. Imagine you're The Honey Badger ... and those jobs? (Wait, what jobs?) Those jobs? Just imagine those jobs are the rats and snakes and larvae The Honey Badger likes to eat. And you just annihilate those applications, like The Honey Badger! Rip 'n shred those motherfuckers!!

Srsly, people, you need to watch this video:

Now, don't you feel better?

The Honey Badger could give a shit about the JIL, and you, friends, need to be a little more like The Honey Badger. Just watch this video. Imagine you're The Honey Badger ... and those jobs? (Wait, what jobs?) Those jobs? Just imagine those jobs are the rats and snakes and larvae The Honey Badger likes to eat. And you just annihilate those applications, like The Honey Badger! Rip 'n shred those motherfuckers!!

Srsly, people, you need to watch this video:

Now, don't you feel better?

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Monday, September 12, 2011

The Insanity of the Academic Job Market

This is yet another phrase that readers have Googled to find this blog, and, truthfully, you could write volumes about the insanity of the academic job market.

And maybe I will give it a good long rant at a later date, but after reading this post today, in which Sisyphus wonders whether a search committee will care if a candidate has ndependently designed yet one more course, after years of adjuncting, I am reminded about one particular type of insanity that the academic job market reproduces year in and year out:

That is, the insanity of believing that you have any degree of control whatsoever over whether a search committee decides you are a good "fit."

Because, beyond reasonable measures like writing a non-stupid cover letter, having the requisite publications, conference presentations, recommendations, and modest teaching experience, there really isn't squat doodle you can do.

Why? Because everyone else has those things, too.

Above and beyond, you cannot anticipate what may or may not stand out to one committee or another. One committee might give you props for that fancy fellowship you got one year, but, alas, that committee isn't searching for a candidate in your field. Another committee might see a particular publication or certain class you taught as beneficial, but, odds are, someone else has similar credentials.

So, people, please stop stressing out and rearranging your lives trying to anticipate what some clueless group of 4-6 people (who don't know you and don't care about you) is going to think of one thing or another on your application. You can beat yourself up believing it might make a difference, but, from what I've observed these past few years, it won't make any.

What matters is this mythical beast called Fit, and, if you are going to cast your fate with the Job Market Gods, you might as well just leave it up to them. There is no point wasting your time and energy trying to determine if planning and prepping that new course in the spring (or whatever it is you think you need to do as job season launches into full swing) will make a difference -- much less actually doing the planning and prepping -- because ONE CLASS after all these years of adjuncting is not going to mean much of anything.

You know what Einstein said about insanity: Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

You may or may not get a committee interested in you this year, but, at this point, if you have several years of adjuncting under your belt (or postdocing or VAPing) it won't be because of any one thing you've done.

And what bothers me most about this particular breed of insanity the academic job market spawns? That it hurts people who seem like otherwise good people, people who not only haven't done anything wrong but have done a good job at their jobs, people who are conscientious teachers, thoughtful scholars, cool colleagues. And it is just totally wrong and insane to reduce them to false hopes and desperation -- and that, through this abuse and exploitation, the system reproduces itself year after year after year after year ... as we all play along ....

It's time to break the cycle.

And maybe I will give it a good long rant at a later date, but after reading this post today, in which Sisyphus wonders whether a search committee will care if a candidate has ndependently designed yet one more course, after years of adjuncting, I am reminded about one particular type of insanity that the academic job market reproduces year in and year out:

That is, the insanity of believing that you have any degree of control whatsoever over whether a search committee decides you are a good "fit."

Because, beyond reasonable measures like writing a non-stupid cover letter, having the requisite publications, conference presentations, recommendations, and modest teaching experience, there really isn't squat doodle you can do.

Why? Because everyone else has those things, too.

Above and beyond, you cannot anticipate what may or may not stand out to one committee or another. One committee might give you props for that fancy fellowship you got one year, but, alas, that committee isn't searching for a candidate in your field. Another committee might see a particular publication or certain class you taught as beneficial, but, odds are, someone else has similar credentials.

So, people, please stop stressing out and rearranging your lives trying to anticipate what some clueless group of 4-6 people (who don't know you and don't care about you) is going to think of one thing or another on your application. You can beat yourself up believing it might make a difference, but, from what I've observed these past few years, it won't make any.

What matters is this mythical beast called Fit, and, if you are going to cast your fate with the Job Market Gods, you might as well just leave it up to them. There is no point wasting your time and energy trying to determine if planning and prepping that new course in the spring (or whatever it is you think you need to do as job season launches into full swing) will make a difference -- much less actually doing the planning and prepping -- because ONE CLASS after all these years of adjuncting is not going to mean much of anything.

You know what Einstein said about insanity: Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

You may or may not get a committee interested in you this year, but, at this point, if you have several years of adjuncting under your belt (or postdocing or VAPing) it won't be because of any one thing you've done.

And what bothers me most about this particular breed of insanity the academic job market spawns? That it hurts people who seem like otherwise good people, people who not only haven't done anything wrong but have done a good job at their jobs, people who are conscientious teachers, thoughtful scholars, cool colleagues. And it is just totally wrong and insane to reduce them to false hopes and desperation -- and that, through this abuse and exploitation, the system reproduces itself year after year after year after year ... as we all play along ....

It's time to break the cycle.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

A Post-Academic Remembers 9/11

Everybody has a story about where they were and what they were doing when they first got the news. I wouldn't really think my story was particularly memorable, except that, in the context of this blog, the fall semester of 2001 was when my entrance to academe conincided with my exit from teaching high school. The experience of 9/11 was very different in those two worlds -- and perhaps I should have recognized it as a sign of things to come.

So, this post isn't really about 9/11 per se, the tragedy, the victims, the political or military fallout (go everywhere else to read about those) -- it's about two ways of responding to "real" world events.

First, some background: In September 2001, I had just begun my first semester as a graduate student. I was in a terminal M.A. program because I wasn't sure that I wanted to go on for a Ph.D. at the time. Technically, I was a full-time graduate student, taking three classes and also working as a T.A. But, in addition, because the T.A. salary was so low and because I wasn't sure where my career was heading, I kept my high school teaching job part-time. Long story short, what this meant was that every morning I taught 11th and 12th grade English at an urban charter school from 8:00 a.m. to noon. Three days out of the week, I left promptly and commuted over to Master's U., where I sat in on the class I was TAing for from 1:00-2:00 and then held office hours. Later, I went to class. On the longest day of the week, I left my house at 7:00 a.m., taught my high school classes, TAed for the college classes, held my office hours, attended grad classes that met from 3:00-6:00 and 6:30-9:30, and got home around 10:00, at which time I settled down for some dinner and a few hours of grading, studying, writing, or prepping for the next morning's classes.

It was exhausting, to say the least, and I quit the high school job at the beginning of spring semester, but here are two vignettes, memories of 9/11, that capture, perhaps, some differences between academic and nonacademic life, differences that have since come to be more important than they seemed at the time.

So, this post isn't really about 9/11 per se, the tragedy, the victims, the political or military fallout (go everywhere else to read about those) -- it's about two ways of responding to "real" world events.

* * * * *

First, some background: In September 2001, I had just begun my first semester as a graduate student. I was in a terminal M.A. program because I wasn't sure that I wanted to go on for a Ph.D. at the time. Technically, I was a full-time graduate student, taking three classes and also working as a T.A. But, in addition, because the T.A. salary was so low and because I wasn't sure where my career was heading, I kept my high school teaching job part-time. Long story short, what this meant was that every morning I taught 11th and 12th grade English at an urban charter school from 8:00 a.m. to noon. Three days out of the week, I left promptly and commuted over to Master's U., where I sat in on the class I was TAing for from 1:00-2:00 and then held office hours. Later, I went to class. On the longest day of the week, I left my house at 7:00 a.m., taught my high school classes, TAed for the college classes, held my office hours, attended grad classes that met from 3:00-6:00 and 6:30-9:30, and got home around 10:00, at which time I settled down for some dinner and a few hours of grading, studying, writing, or prepping for the next morning's classes.

It was exhausting, to say the least, and I quit the high school job at the beginning of spring semester, but here are two vignettes, memories of 9/11, that capture, perhaps, some differences between academic and nonacademic life, differences that have since come to be more important than they seemed at the time.

* * * * *

A little after 9:00 a.m. on Tuesday, September 11, 2001, I was sitting at my desk in a windowless classroom in a rundown school building east of the Anacostia River. While I was going over lesson plans, my 11th graders were, more or less quietly, taking a quiz.

All of a sudden, I hear some shouting and door slamming in the hall. Oh no, I think to myself. What now? My students -- mostly at-risk kids who hadn't done so well in the regular public schools -- were easily distracted, and some disturbance in the hall could easily disrupt the entire class period's plans. We'd have to redo the quiz at the very least ...

Just as I'm having these thoughts and noticing my students looking up from their quizzes and rolling their eyes at each other, the door to my classroom bursts open, as Crazy Kid sticks his head in and shouts at the top of his lungs, "We're under attaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaack!! Y'all better take COVER, WE"RE UNDER ATTAAAAAAAAACK!!!!!!"

He slams the door and runs down the hall, and I hear him do the same thing to the classroom next door.

Not entirely surprising. Crazy Kid is known for his antics and interruptions. But. Great. Now my students are all talking to each other, yelling stuff back at Crazy Kid (who is truly insane and spends more time in the halls and the principal's office than in class):

"What the fuck?!"

"Yo, what Crazy Kid be smokin' today?"

"You muthafuckahs, shut the fuck up. I'm tryin' to take my quiz, yo!"

"Ms. Future Recent Ph.D., you gonna do something about Crazy Kid? He sound like he need some help today, like he ain't take his medication or somethin' '" (some whistling and high fives all around for this crack -- Crazy Kid usually gets his due with or without teacher interference).

"Ahem. Settle down, everybody, please. Crazy Kid is not in our class, and I'm sure Mr. Hall Monitor will make sure Crazy Kid is taken care of. Now, please, let's get back to those quizzes."

So, they start to settle down. Papers rustle. Pencils start scratching away. A few muffled comments are whispered to stifled laughter.

We can still hear Crazy Kid out in the hall arguing with Hall Monitor and Assistant Principal, but then ... there's an announcement over the P.A. system:

"Teachers, please keep your students in class with your doors locked until further notice. There has been a suspected terrorist attack. The safest place for you and your students is in your classrooms. The building is on lockdown until further notice. We will keep you informed as details become available."

My students and I just look at each other. One kid asks, quite seriously, "Does this mean we still have to take the quiz?"

And then more information starts to emerge. There is another P.A. announcement. The World Trade Center. The Pentagon. Parents will be contacted. Arrangements will be made. In the meantime, an hour later, we're still on lockdown in the classroom, and everyone's getting restless. One kid asks if he can go to the bathroom, and I let him go. We wait anxiously to see what news he will return with.

He returns fifteen minutes later with a radio! I have no idea where he got it, and he won't say. We all huddle around the radio and listen, hardly talking ... except, the mother of one of the kids works at the Pentagon, and he's starting to freak out ... and he says he has to go to the office and see if he can get in touch with her ... he doesn't care if he gets in trouble for leaving class ... and so he leaves and doesn't come back ...

And, when he goes, it's as if the reailty of the situation is finally starting to sink in. The kids are visibly worried about what's going on, and I have no idea what to tell them. These are tough kids in a tough neighborhood. They're used to violence. The last time we were on lockdown was when a car filled with suspected gang members, visibly armed, was slowly driving in circles around the school for nearly an hour before police got it to move away.

But this is different. As we listen to the radio, "Do you think we'll be next?" one kid asks, "Do you think the terrorists will come after us? Do you think they'll bomb the rest of the city? Do they have nukes?"

Another kid answers, "Naw, dawg, don't no terrorists care 'bout poor black people. Naw, not when they can blow up rich white people. We 'bout in the safest place we can be out here!!"

* * * * *

Eventually, lockdown ended. Everyone got home safely. The kid's mother who worked at the Pentagon was OK.

But there was no school the next day ... This charter school was run by retired military and drew a fair percentage of its students from the nearby military base. The kid in my class wasn't the only one with a parent who worked at the Pentagon ...

Everyone, whether neighborhood kids or base kids, needed time to process. Their reactions were visceral and fundamental:

Who are we? What is our relationship to the world outside the microcosms of home and school? Has that relationship changed? What does the rest of the world think of us? Who are we as Americans -- in general and as a specific group marginalized by race and class? How are we united? How are we divided? What does the future hold? What is our role to be?

* * * * *

At Master's U., classes for the rest of the day were cancelled, but the next day, the university was open. Professors could make their own decisions about whether to hold classes or not. Old and Boring Theory Prof decided to hold class.

No one could think of anything but the attacks of the previous day, but we didn't talk about it. Old and Boring Theory Prof sat and read from his notes of thirty years ago, as he did every week, and we sat and listened and took notes for three hours. No one said anything or expressed any emotion.

It was as though nothing at all had happened.

* * * * *

Until MLA, that is. There've been plenty of panels devoted to the subject in the ten years since.

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

"how to quit adjuncting"

According to my traffic stats, lots of you readers find this blog by Googling that phrase or something like it. However, I don't think I've actually ever addressed the "how to" question directly. Here goes:

If you're asking "how to quit adjuncting," the odds are you've been trapped in academe for a long time and that academe has distorted your perceptions of what your options are both inside and outside academe.

This distortion, though, is not your fault -- it's just academe being academe, poisoning your perception of your status as an adjunct by making you believe that, if you stick it out for just a little while longer, things will get better, a tenure-track "real" job will come along, while at the same time making you believe things would be even worse if you were to quit and find a nonacademic job. This is how academe has ended up with such a willing and seemingly endless supply of adjuncts -- that is, by making you believe that adjuncting is your best and only option.

It's a good thing you're starting to resist. Asking "how to quit adjuncting" is the right thing to do. I was asking myself that question right about this time -- maybe a little closer to November when I knew nothing had come of my academic job search -- just one year ago.

I don't have any magic, sure fire advice here that will work for everyone in every situation, but here are some tips, based on my experience, to help you quit adjuncting:

Decide when you're going to quit.

While that may seem obvious, there's a difference between telling yourself "I want to quit" or "I should quit" or "I can't stand this adjunct hell I'm stuck in and I really need to quit" and actually making the decision to do so. If you don't commit yourself to a decision about when you're going to quit, you're less likely to take the appropriate steps to make quitting something you CAN do, both emotionally and financially speaking, in terms of finding your next job. So decide when and start planning for it.

Right now would be an optimal time to plan to quit at the end of this semester that is just now getting under way. Last year, what I decided was this: I would do another tenure-track job search. If I landed any interviews that would leave open the possibility of a tt job this fall, I would continue to adjunct through the spring. If I didn't have any prospects, I would quit, ideally finding a new, nonacademic job in between fall and spring semesters. When November rolled around and nobody had called inviting me for an MLA interview, I started looking for that new, nonacademic job in earnest. I had a few interviews and started my current job at the end of January, a week before spring classes started.

Decide if you'd be willing to quit in the middle of a semester and under what circumstances.

When it comes to looking for your next job, the academic calendar is a pain in the ass. The nonacademic world has no regard for the beginnings and endings of semesters, but if you're serious about quitting adjuncting, you have to be mentally prepared to jump ship in the middle of a semester if the right opportunity comes along. No, quitting mid semester is less than ideal, but you might have to do it -- or face being stuck adjuncting for yet another semester if another nonacademic job offer doesn't come along.

Look at it this way: Academe doesn't care about you. They'll find a replacement. Your students will survive. Academe is paying you shit and treating you like shit for the "opportunity" to work in a profession that offers you no long-term career prospects and not a hell of a lot in the short-term, either -- you can't even count on having a job as an adjunct next semester. Not only should your department not be surprised by your quitting mid semester, if you have to, but they should expect it to happen more often than it does.

Remember that your semesterly adjunct contract is hardly binding. All it stipulates is that you have to show up to class for the required number of days in order to collect your miserable paycheck. If you don't show up to class -- because you quit -- you don't get paid. It's that simple. Don't ever expect to teach in that department again if you do quit mid semester, but otherwise, you owe them nothing. They're not going to sue you for quitting. It's a matter of rational self-interest, so, if you have to, just do it. And feel no guilt whatsoever. You will be forgotten as soon as they hire some other poor sucker to replace you, which they very quickly will.

Here was my logic on the mid semester question: Ideally, I wanted to quit between semesters, and, ultimately, that worked out for me. However, I did quit only a week before spring classes started, after I had signed a spring semester contract (and, as I've blogged before, they were already asking me back in the fall six weeks after I'd quit!), and I was mentally prepared to walk away mid semester if the right opportunity came along. What I mean by "right opportunity" was a job with a particular minimum salary (a little higher than what I'm currently earning but based aggregately on the jobs I'd been applying for) that would allow me to feel good about saying to Scheduler of Adjuncts, "I'm sorry to walk out on you mid semester like this, but Employer X has offered me a job that pays Y. Given what you're paying me as an adjunct, I can't afford to say no." So, I wouldn't have walked away mid semester for just anything, but I was willing to do it. Decide what "right opportunity" means for you and don't be afraid to quit mid semester if it comes along.

When you're looking at those job ads, consider that there are things you might be good at -- and that you should apply for -- that you may not have thought you'd be good at or would even want to do while you fancied you had a future in academe.

Obviously, you don't want to get into something that's WORSE than adjunct hell, but you're not going to be applying for jobs at a meat-packing plant. And, if you think being on your feet all day would be a worse hell than adjunct hell, don't apply for retail or waiter/waitress jobs. Most likely, you're going to end up at a job in an office, ideally one that has some promotion potential. But what can you do in an office? How are you, as a recovering academic, going to compete with all the job applicants that have already worked in a similar type of job? How do your skills hold up against what the job description says you need?

I'll get to that in a minute ...

There are plenty of blogs, books, and advice forums out there that address the issue of what nonacademic work you can do with a graduate degree in the humanities, so I'm not going to get into specifics. But what I will say is to keep your options open. As JC has pointed out frequently and rightly, this next job is just that -- a "next" job, not a "forever" job. You don't have to be especially committed to it or the industry or the type of work. For the time being, you just need something that's going to get you out of adjunct hell. And that's pretty much ... well, a lot of things.

Just to get you thinking, here are a few: writer/editor (lots of different types in many industries), development specialist/associate/coordinator etc. (if you're good at talking to people about causes/issues you care about and have no problem asking for money to support them, look into development positions at nonprofits), program coordinator, management analyst, administrative assistant/associate/specialist (yes, all of them), executive assistant (like an admin asst but requires more refinement, which you have, and can pay pretty well in some industries), communications assistant/associate/specialist etc. (similar to some writer/editor jobs but usually requires more tech skills as well as in-person communications skills, but, hey, you've spent years in front of a class!), corporate trainer (you learn stuff and then teach it to others), and on and on ...

So, but the scarier questions you might be asking are: "How do I explain, on the one hand, that I have the skills they're looking for but, on the other hand, I have no experience at all actually working as an administrative whatever-the-fuck? How do I explain this odd imbalance in a one-page cover letter? (yes, I did say one page -- none of this 2-3 page academic cover letter bluster.) How do I make myself look like I have something to offer them more than sheer desperation?"

Market yourself as a career changer.

I'm not even going to elaborate on this much because it's such a simple concept. Nonacademics understand the concept of career change much better than they can grasp why some dumbshit nerd like you would spend an extra decade "in school" only to come out at the end with no job prospects. You need to tell them that, while you spent 10 years as an educator (a teacher, NOT a student -- yes, you were in graduate school, but that was a matter of professional development) and while this was a job you very much enjoyed and excelled at, your professional and personal goals have changed over time. You are now seeking other opportunities, developing other interests, and looking for new ways to use the talents you've acquired through your experience in the education industry. In other words, you have a lot to offer.

Once I started writing cover letters describing myself as a career changer, I started getting calls for interviews.

If you're asking "how to quit adjuncting," the odds are you've been trapped in academe for a long time and that academe has distorted your perceptions of what your options are both inside and outside academe.

This distortion, though, is not your fault -- it's just academe being academe, poisoning your perception of your status as an adjunct by making you believe that, if you stick it out for just a little while longer, things will get better, a tenure-track "real" job will come along, while at the same time making you believe things would be even worse if you were to quit and find a nonacademic job. This is how academe has ended up with such a willing and seemingly endless supply of adjuncts -- that is, by making you believe that adjuncting is your best and only option.

It's a good thing you're starting to resist. Asking "how to quit adjuncting" is the right thing to do. I was asking myself that question right about this time -- maybe a little closer to November when I knew nothing had come of my academic job search -- just one year ago.

I don't have any magic, sure fire advice here that will work for everyone in every situation, but here are some tips, based on my experience, to help you quit adjuncting:

Decide when you're going to quit.

While that may seem obvious, there's a difference between telling yourself "I want to quit" or "I should quit" or "I can't stand this adjunct hell I'm stuck in and I really need to quit" and actually making the decision to do so. If you don't commit yourself to a decision about when you're going to quit, you're less likely to take the appropriate steps to make quitting something you CAN do, both emotionally and financially speaking, in terms of finding your next job. So decide when and start planning for it.

Right now would be an optimal time to plan to quit at the end of this semester that is just now getting under way. Last year, what I decided was this: I would do another tenure-track job search. If I landed any interviews that would leave open the possibility of a tt job this fall, I would continue to adjunct through the spring. If I didn't have any prospects, I would quit, ideally finding a new, nonacademic job in between fall and spring semesters. When November rolled around and nobody had called inviting me for an MLA interview, I started looking for that new, nonacademic job in earnest. I had a few interviews and started my current job at the end of January, a week before spring classes started.

Decide if you'd be willing to quit in the middle of a semester and under what circumstances.

When it comes to looking for your next job, the academic calendar is a pain in the ass. The nonacademic world has no regard for the beginnings and endings of semesters, but if you're serious about quitting adjuncting, you have to be mentally prepared to jump ship in the middle of a semester if the right opportunity comes along. No, quitting mid semester is less than ideal, but you might have to do it -- or face being stuck adjuncting for yet another semester if another nonacademic job offer doesn't come along.

Look at it this way: Academe doesn't care about you. They'll find a replacement. Your students will survive. Academe is paying you shit and treating you like shit for the "opportunity" to work in a profession that offers you no long-term career prospects and not a hell of a lot in the short-term, either -- you can't even count on having a job as an adjunct next semester. Not only should your department not be surprised by your quitting mid semester, if you have to, but they should expect it to happen more often than it does.

Remember that your semesterly adjunct contract is hardly binding. All it stipulates is that you have to show up to class for the required number of days in order to collect your miserable paycheck. If you don't show up to class -- because you quit -- you don't get paid. It's that simple. Don't ever expect to teach in that department again if you do quit mid semester, but otherwise, you owe them nothing. They're not going to sue you for quitting. It's a matter of rational self-interest, so, if you have to, just do it. And feel no guilt whatsoever. You will be forgotten as soon as they hire some other poor sucker to replace you, which they very quickly will.

Here was my logic on the mid semester question: Ideally, I wanted to quit between semesters, and, ultimately, that worked out for me. However, I did quit only a week before spring classes started, after I had signed a spring semester contract (and, as I've blogged before, they were already asking me back in the fall six weeks after I'd quit!), and I was mentally prepared to walk away mid semester if the right opportunity came along. What I mean by "right opportunity" was a job with a particular minimum salary (a little higher than what I'm currently earning but based aggregately on the jobs I'd been applying for) that would allow me to feel good about saying to Scheduler of Adjuncts, "I'm sorry to walk out on you mid semester like this, but Employer X has offered me a job that pays Y. Given what you're paying me as an adjunct, I can't afford to say no." So, I wouldn't have walked away mid semester for just anything, but I was willing to do it. Decide what "right opportunity" means for you and don't be afraid to quit mid semester if it comes along.

When you're looking at those job ads, consider that there are things you might be good at -- and that you should apply for -- that you may not have thought you'd be good at or would even want to do while you fancied you had a future in academe.

Obviously, you don't want to get into something that's WORSE than adjunct hell, but you're not going to be applying for jobs at a meat-packing plant. And, if you think being on your feet all day would be a worse hell than adjunct hell, don't apply for retail or waiter/waitress jobs. Most likely, you're going to end up at a job in an office, ideally one that has some promotion potential. But what can you do in an office? How are you, as a recovering academic, going to compete with all the job applicants that have already worked in a similar type of job? How do your skills hold up against what the job description says you need?

I'll get to that in a minute ...

There are plenty of blogs, books, and advice forums out there that address the issue of what nonacademic work you can do with a graduate degree in the humanities, so I'm not going to get into specifics. But what I will say is to keep your options open. As JC has pointed out frequently and rightly, this next job is just that -- a "next" job, not a "forever" job. You don't have to be especially committed to it or the industry or the type of work. For the time being, you just need something that's going to get you out of adjunct hell. And that's pretty much ... well, a lot of things.

Just to get you thinking, here are a few: writer/editor (lots of different types in many industries), development specialist/associate/coordinator etc. (if you're good at talking to people about causes/issues you care about and have no problem asking for money to support them, look into development positions at nonprofits), program coordinator, management analyst, administrative assistant/associate/specialist (yes, all of them), executive assistant (like an admin asst but requires more refinement, which you have, and can pay pretty well in some industries), communications assistant/associate/specialist etc. (similar to some writer/editor jobs but usually requires more tech skills as well as in-person communications skills, but, hey, you've spent years in front of a class!), corporate trainer (you learn stuff and then teach it to others), and on and on ...

So, but the scarier questions you might be asking are: "How do I explain, on the one hand, that I have the skills they're looking for but, on the other hand, I have no experience at all actually working as an administrative whatever-the-fuck? How do I explain this odd imbalance in a one-page cover letter? (yes, I did say one page -- none of this 2-3 page academic cover letter bluster.) How do I make myself look like I have something to offer them more than sheer desperation?"

Market yourself as a career changer.

I'm not even going to elaborate on this much because it's such a simple concept. Nonacademics understand the concept of career change much better than they can grasp why some dumbshit nerd like you would spend an extra decade "in school" only to come out at the end with no job prospects. You need to tell them that, while you spent 10 years as an educator (a teacher, NOT a student -- yes, you were in graduate school, but that was a matter of professional development) and while this was a job you very much enjoyed and excelled at, your professional and personal goals have changed over time. You are now seeking other opportunities, developing other interests, and looking for new ways to use the talents you've acquired through your experience in the education industry. In other words, you have a lot to offer.

Once I started writing cover letters describing myself as a career changer, I started getting calls for interviews.

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Lions and Tigers and ... Bears?! Holy $hit, A BEAR!!!

Yesterday, Peaches and I were enjoying a nice day of hiking (basically, where our "staycation" ended up) in Shenandoah National Park. It was a bit misty:

I took that one out the car window at one of the "scenic overlooks" along Skyline Drive, but the clouds and mist kept things reasonably bearable (pun intended) on the trails on what would otherwise have been a too hot day.

The deer even came up close enough to photograph:

I know you rural and even suburbia people aren't that excited about deer (they eat your geraniums and whatnot), but they're a novelty for us city folk.

Another, slightly scarier novelty of woodland critterdom, of course, are the bears, black bears, to be specific.

As we were hiking back along a lonely stretch of trail, we were nearly scared out of our wits when we SAW ONE, NOT TWENTY FEET AWAY!!! He (or she) was in the woods, just off the trail to our right and was looking right back at us!!!

Oh, you know for sure I'd have a picture, but we weren't sure what to do and getting the heck away from there as quickly as possible, before that bear got any ideas, was what we did.

Too bad, because as it turns out, black bears are rarely dangerous to humans. Here is a visual:

I didn't take this picture, but the bear here looks very much like the bear we saw. Scary, no? But I guess, they're not prone to attacking ... next time, I will take my own.

The feeling of looking at another creature like that, though, sizing him up as he does the same to you, one animal to another, is something pretty spectacular. You don't have any particular advantage for being human, especially if you don't know anything at the time about the other creature's habits and behavior ...

Faulkner, in that great and terrible tale about the bear and the boy, puts it this way:

I took that one out the car window at one of the "scenic overlooks" along Skyline Drive, but the clouds and mist kept things reasonably bearable (pun intended) on the trails on what would otherwise have been a too hot day.

The deer even came up close enough to photograph:

I know you rural and even suburbia people aren't that excited about deer (they eat your geraniums and whatnot), but they're a novelty for us city folk.

Another, slightly scarier novelty of woodland critterdom, of course, are the bears, black bears, to be specific.

As we were hiking back along a lonely stretch of trail, we were nearly scared out of our wits when we SAW ONE, NOT TWENTY FEET AWAY!!! He (or she) was in the woods, just off the trail to our right and was looking right back at us!!!

Oh, you know for sure I'd have a picture, but we weren't sure what to do and getting the heck away from there as quickly as possible, before that bear got any ideas, was what we did.

Too bad, because as it turns out, black bears are rarely dangerous to humans. Here is a visual:

|

| Via |

The feeling of looking at another creature like that, though, sizing him up as he does the same to you, one animal to another, is something pretty spectacular. You don't have any particular advantage for being human, especially if you don't know anything at the time about the other creature's habits and behavior ...

Faulkner, in that great and terrible tale about the bear and the boy, puts it this way:

Then he saw the bear. It did not emerge, appear: it was just there, immobile, fixed in the green and windless noon's hot dappling, not as big as he had dreamed it but as big as he had expected, bigger, dimensionless against the dappled obscurity, looking at him.

Go Down, Moses (1940)

Thursday, September 1, 2011

Stories Old Houses Tell

I could (should) be cleaning my house right now, but I'd rather tell you about it than deal with it. Its history is more interesting -- such as I can piece together anyway -- than its present.

Our house was built in 1916. It's one of those old rowhouses one finds in many cities on the East Coast. Brick. Sturdy. More or less spacious if you have the whole thing to yourself, as far as urban living goes. Many similar houses in our neighborhood have had their insides demolished and rebuilt into condos -- one condo per floor that, these days, cost more than we paid for the entire house back in 2002.

I used to turn up my nose at all that expensive refurbishing. Who would want something small and pricey that had had all of its history destroyed if one could have something three times the size with most of its original detail -- with relics from its original owners, from nearly a hundred years ago, still remaining up in the attic?

Peaches and I were both pretty naive. Yes, the house was a good investment, but we had no idea how much work and cost it would take to maintain -- and how unequal to the task we would prove to be. In the first few years, Peaches did some re-wiring (the electrical system hadn't been updated, the inspector told us, since the 1930s); I painted the bathroom. And then we sort of realized that neither one of us was really that into (or good at, on my part) home improvement projects. And so, yes, we have beautiful hardwood floors and molding around the windows and doorways and baseboards, and we have a cool clawfoot bathtub and a beautiful pocket door ...

You can see the beautiful wood trim but also where the plaster has come down, more than once. And then there's the brick work both outside and in the basement (right now, we're just doing the floor in the basement -- bricks will have to wait), the 100-year-old windows, the plumbing, the porch, the roof ...

Sigh. Those renovated condos start to look pretty good.

Except, what you will never find in a renovated condo is something like this:

We found this painting up in the attic when we moved in, along with some old furniture, a candelabra, about a dozen empty antique Jack Daniels bottles, and a stack of dental books from the 1920s.

Who is the woman in the painting? Who painted her? Who sat up in the attic studying by candlelight to become a dentist at a famous Historically Black College, in a segregated city, drinking whiskey and dreaming about the future across the rooftops on warm breezy nights?